Is It Time to Stop Blaming Colonial Mentality for Everything Wrong With Us?

Ok but hear us out: maybe the real work isn’t about blame or relearning history, but about building who we want to be next.

Written by Clifford Temprosa

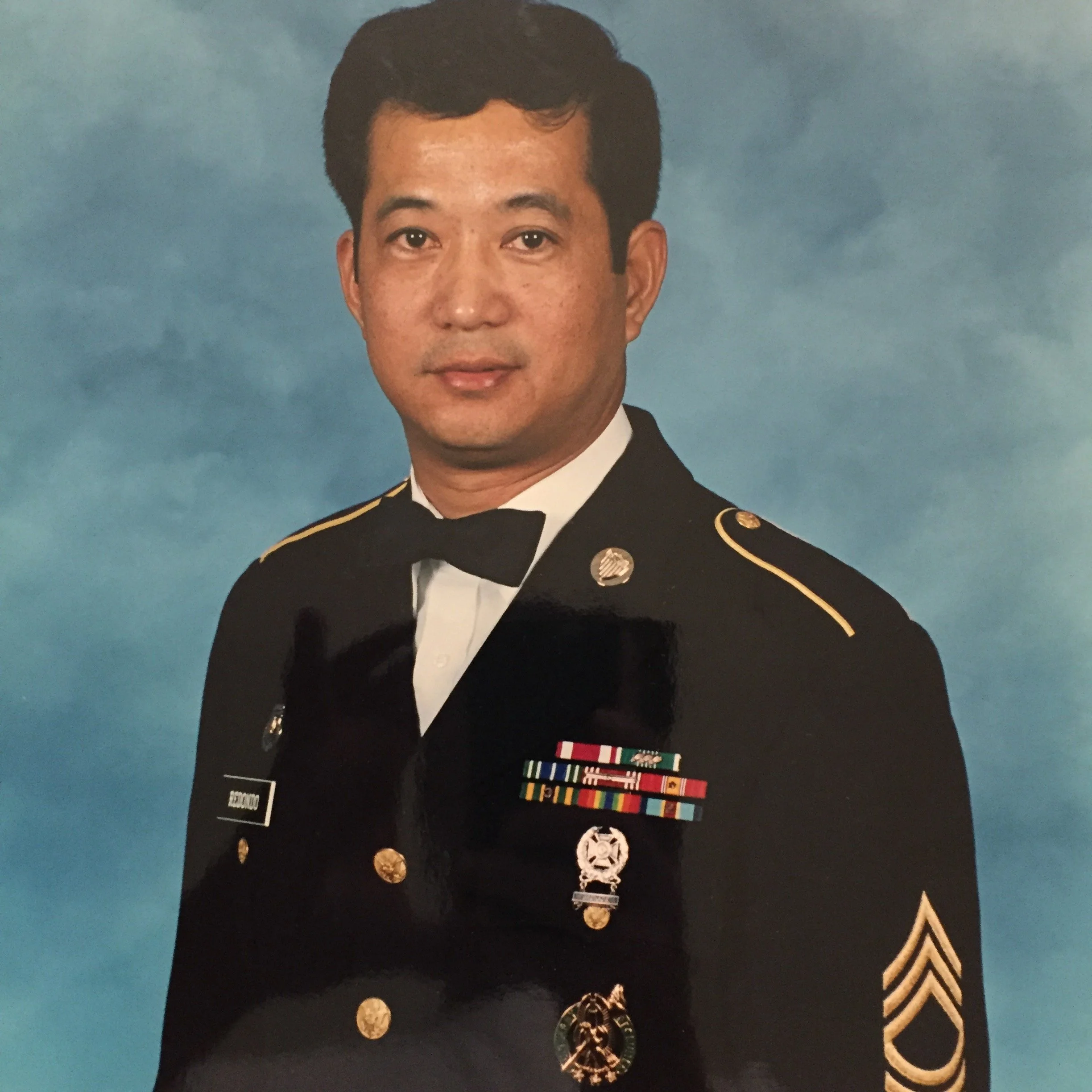

The Family Photo

In every Filipino family photo, there’s always that one relative who says, “Mas maputi ka na ngayon!” — as if fairness were a blessing, a reward, a marker of improvement.

I used to laugh it off. Until I realized it wasn’t just a joke - it was a symptom. A whisper from generations trained to see beauty through the eyes of empire.

We call it colonial mentality - that inherited belief that foreign is better, that whiteness is worth aspiring to, that our own worth is measured by proximity to something imported. It’s the phrase we reach for when trying to explain the quiet contradictions of being Filipino: proud of who we are, yet perpetually chasing the validation of someone else’s approval.

But when a phrase becomes too convenient, it starts to lose its power. When every insecurity and inequality is blamed on colonial mentality, we stop looking inward. We start reciting history instead of rewriting it.

At some point, colonial mentality stops being history, it becomes habit. And habit, unlike history, doesn’t end on its own. It must be unlearned, replaced, and transformed.

Roots and Rupture: How the Empire Lived On

Spain gave us religion. America gave us aspiration. Both gave us amnesia.

Four hundred years of empire did not just conquer our islands - it colonized our imagination. Under Spain, we learned to kneel before whiteness as a form of salvation. Under America, we were told democracy was a gift, not something we could ever author.

We learned to pray to a white Christ and call it holiness. We learned to study in a foreign language and call it intelligence. We learned to mimic and call it mastery.

When independence came in 1946, the colonial government left, but the colonial framework stayed. The same schools, the same churches, the same elite structures carried on, rebuilt by Filipino hands but powered by the same ideals of subservience and mimicry.

We were no longer colonized by force, but by familiarity. The empire had left its ghost, and we mistook the ghost for ourselves.

Today, colonialism is no longer a political structure. It is cultural muscle memory - reflexive, invisible, and inherited. And yet, even in its endurance, it does not tell the full story of who we have become.

When Awareness Becomes Performance

“Decolonization” has become one of the most shared, hashtagged, and merchandised words in modern Filipino discourse. But awareness is not the same as transformation.

We share Instagram posts about pre-colonial babaylans and feminist ancestors, yet silence women who speak too loudly in meetings. We host “Proudly Pinoy” galas in five-star hotels but still treat local brands as charity, not choice.

We perform identity like a costume instead of a commitment. We mistake representation for revolution.

Colonial mentality used to look like self-hate, now it looks like self-promotion. We call it “decolonizing,” but often what we’re really doing is rebranding.

We celebrate Filipino pride when it’s televised, when it trends, when it earns applause from those we once called colonizers. But what does pride look like when no one is watching? When it doesn’t sell? When it requires accountability, not aesthetics?

Real decolonization is not an aesthetic. It’s a discipline. It is the willingness to reexamine everything we’ve inherited — not to romanticize the past, but to reconstruct the present.

Colorism: The Empire Under Our Skin

In every Filipino drugstore, there’s an aisle that sells transformation in a bottle. Gluta. Kojic. Papaya.

These products promise more than clear skin - they promise access. Access to confidence. To class. To belonging.

Colorism is the empire’s most durable export. Centuries after Spain divided us by mestizo and indio, and America reinforced those categories with English and cinema, we continue to enforce the same hierarchies on each other.

The tragedy is not just that we lighten our skin - it’s that we darken our worth.

In the diaspora, the habit travels with us. Walk into Filipino stores in Los Angeles, Toronto, or Dubai, and you’ll find the same whitening soaps lined up neatly, shipped from the homeland as though self-erasure were part of the care package.

But here’s the complexity: colorism doesn’t survive because of colonizers. It survives because we, the colonized, keep buying, believing, and broadcasting it.

Empire didn’t just shape how we look. It shaped how we see.

Class, Language, and the Myth of Refinement

“Speak English properly,” Filipino parents still say, as if accent were morality and articulation were character.

In our schools, the child who speaks English well is called “smart.” The one who struggles is called “barok.” Even our humor reinforces the divide, we laugh at the probinsyano accent, we imitate the jejemon, we scold the domestic worker for “broken grammar.”

The colonial blueprint taught us to associate sophistication with distance - from labor, from the land, from language. And we have perfected that system ourselves.

In the diaspora, these hierarchies persist in subtler ways. Filipino nurses and engineers share break rooms, yet their kids attend different schools. “American-born” becomes a social class, not a birthplace. Tagalog becomes a secret code - spoken proudly in karaoke rooms but carefully avoided in offices.

The truth is, the mestizo ideal never disappeared. It simply switched its vocabulary, from skin to education, from accent to affiliation. We no longer bow to the colonizer, but we’ve learned to imitate him so well that we sometimes forget who’s in control.

The Politics of Blame

“Colonial mentality” once helped us name the lingering weight of empire. It allowed generations to see how oppression outlasted occupation. But over time, the term has become a crutch, a default explanation that excuses stagnation.

We say: Why don’t Filipinos trust local talent? Colonial mentality. Why do our leaders lack vision? Colonial mentality. Why do we envy our neighbors? Colonial mentality. Why are we on Filipino time. Colonial mentality.Why do we prefer whiteness?. Colonial mentality.

It’s a lazy diagnosis for a complex disease.

When we treat history as destiny, we surrender agency. When we name the trauma but refuse the therapy, we turn awareness into avoidance. Yes, colonization shaped us. But so did resistance. So did survival. So did innovation.

The harder truth is this: the empire may have left, but the elite structures it built — of beauty, religion, governance, and class — are now guarded by Filipinos themselves. And so long as we keep blaming ghosts, we will never confront the systems we’ve built in their image.

The Hard Truth

And here’s the hard truth: it’s okay to say that yes, this is who we are — and it is not colonialism.

Some of our values, habits, and ways of being are not products of oppression, but of evolution. Not every Western influence is a wound. Some became our own through adaptation, innovation, and choice.

We have made the colonizer’s language sing in the rhythm of our islands. We have turned Catholic ritual into community celebration, where devotion is accompanied by laughter, dancing, and food. We have used English not to erase our native tongues but to tell our stories to the world on our own terms.

To call all of that “colonial” is to deny ourselves agency — to erase the creativity with which Filipinos have remixed, reclaimed, and redefined what was once imposed.

The danger is in assuming that everything foreign is corrupt and everything native is pure. Purity is not power — discernment is.

Our culture is not a crime scene; it’s a collage. A living, breathing synthesis of survival and self-invention.

To heal, we must stop obsessing over what was borrowed, and start celebrating what was transformed.

We are not trapped between authenticity and betrayal. We are what we’ve made of everything that tried to make us.

A Breath Between Blame and Becoming

Maybe it’s time to admit that liberation isn’t about going backward, it’s about going deeper. Decolonization isn’t an act of erasure; it’s an act of authorship. We inherit what we did not choose, but we get to choose how to live with it. Our history will always speak but the question is: who holds the microphone now?

Between Healing and Accountability

Healing begins with naming, but it matures with changing. It is not enough to say we’ve been colonized; we must ask how we continue to colonize ourselves.

Ask: How do our schools still teach history through the lens of conquerors? How do our media outlets still praise Eurocentric beauty? How do our families still silence children in the name of hiya?

Accountability is the next step in decolonization. It means confronting not only who hurt us — but who we’ve become in their absence.

True cultural healing means learning to critique without self-loathing, to love without romanticizing, and to honor the past without worshiping it.

To decolonize is not to purify, it is to practice power with consciousness.

The Diaspora’s Dilemma

Across America, the Filipino diaspora carries this contradiction like luggage: We are both the most visible and the most invisible Asian group. We are proud, yet peripheral.

We raise flags every October, yet stay silent when the U.S. government funds wars that harm the Global South. We celebrate our parents’ sacrifices, yet mock their accents. We call our dual identity strength, but sometimes, it’s just confusion with better vocabulary.

Many Filipino Americans mistake visibility for liberation. We think the more we appear on television, the freer we become. But visibility without voice is performance, not power.

Colonial mentality in the diaspora isn’t just about admiration for the West — it’s about fear of being forgotten without it.

Even in 2025, we still see it in our screens and feeds: the TikTok creator who jokes about brownness for virality, the influencer who only mentions heritage when it’s profitable, the workplace that celebrates “diversity” but sidelines Filipino leadership.

The task before us is authorship. To stop existing as a footnote in someone else’s story — and to start writing our own.

From Pain to Power

Filipino pride cannot rest only on our survival; it must stand on our self-determination.

Our power is not in how much pain we’ve endured, but in how we’ve turned that pain into purpose.

When our nurses lead global health systems, when our filmmakers like Lav Diaz and Isabel Sandoval redefine cinema, when our farmers champion food sovereignty, and our youth march for climate justice - that is not mimicry. That is mastery.

That is Filipino pride unshackled from suffering. Pain may have birthed our movements, but progress must raise them.

Global Parallels: Shared Ghosts

This story isn’t ours alone.

Indians still wrestle with English as the language of both access and alienation. Jamaicans still measure class through accent and proximity to British manners. Vietnamese and Indonesians still navigate between colonial memory and capitalist modernity.

Across the postcolonial world, the same ghosts linger but some have learned to live with them, to dance with them, to build futures out of their remains.

We share a global condition — the afterlife of empire. But how we inhabit that afterlife defines whether we remain haunted or become whole.

The Mirror and the Map

We’ve stared into the mirror long enough. It’s time to use it as a map.

When I look at that family photo now, I still see traces of empire — the whitening filters, the Western smiles, the subtle longing for light. But I also see joy. Humor. Resilience. The defiant beauty of people who refuse to disappear.

The empire may have written the first draft. But we are writing the next chapter — in our own handwriting.

Because colonial mentality isn’t destiny. It’s a habit we can unlearn.

And when we finally stop calling everything colonial, we will see what we’ve always been not imitators, not victims, but inventors of our own freedom.

The Call to Action: What Cultural Accountability Looks Like Now

So what does cultural accountability look like on the ground — in 2025 and beyond? It’s universities teaching Philippine Studies not as nostalgia, but as national strategy. It’s diaspora nonprofits shifting from cultural festivals to civic campaigns. It’s Filipino-owned media pushing back on colorism and classism in their casting rooms. It’s parents teaching their children that kindness is intelligence. It’s young entrepreneurs building brands that celebrate brownness not as resistance, but as normalcy. It’s policymakers recognizing that language access, mental health, and representation are not extras — they are equity.

Cultural accountability is not an academic idea. It’s every small choice that teaches the next generation that loving yourself is not rebellion — it’s responsibility.

Accountability doesn’t mean control. In our pursuit of cultural healing, we must resist turning liberation into another checklist. Some of what we call “colonial” is not corruption, but complexity, a reflection of how the world has intertwined us with others. The goal is not to erase influence, but to understand it without shame.

The Complexity of Choice: When Preference Isn’t Betrayal

We also have to accept that not everything we call colonial mentality is a moral failure. Sometimes, it’s just preference — shaped by history, yes, but still personal.

The truth is, not every attraction to whiteness, foreignness, or modernity is self-hate. For some families, these preferences come from stories of survival — parents who equated English fluency with safety, or migration with opportunity. For others, it’s aesthetic, experiential, or emotional — the result of global exposure, not necessarily internalized shame.

We cannot decolonize by policing desire. We cannot preach liberation while condemning people for what they find beautiful, familiar, or aspirational.

To hold every choice hostage to ideology is to strip people of their humanity — the same mistake colonizers once made.

Cultural maturity means learning to tell the difference between internalized hierarchy and individual autonomy. It means knowing that liberation is not about enforcing uniformity of taste, but expanding the freedom to choose without fear of judgment.

Because accountability without empathy becomes another form of control. And decolonization without compassion becomes its own kind of dogma.

If we truly seek to liberate the Filipino mind, we must also learn to release each other from purity tests. To honor that one can love a foreign culture without betraying their own. To understand that not every choice that looks “Western” is a wound, sometimes it’s just a world expanded.

Real pride doesn’t require purity. It requires permission - to be complex, to evolve, to belong to more than one story at once.

A Thought For The Diaspora

It’s easier to debate decolonization from New York than to survive it in Manila. For many Filipinos, whitening soap isn’t ideology — it’s economy. English fluency isn’t pride — it’s paycheck. We cannot shame those who make practical choices within unequal systems. If we are to talk about liberation, we must first talk about the unequal access to it. Real decolonization requires empathy for the conditions that shape people’s realities. Not judgment for how they navigate them.

At the heart of it all, decolonization is not destruction. It's devotion. Love is the quiet rebellion that history could never conquer. To love being Filipino — in every flawed, hybrid, ever-evolving sense — is to choose life over shame, tenderness over theory. Love is not the absence of critique; it’s the courage to build something beautiful after critique. It’s the art of holding complexity without fear.

After All the Mirrors Break

Maybe the point was never to escape the shadow of the empire, but to stop mistaking the shadow for ourselves. Because even after the mirrors break, the light remains.

We are more than the histories that haunt us and the habits that hold us. We are the laughter that survived them.

The work of being Filipino is not to perfect our reflection - it is to live fully in our contradictions, to be both question and answer, to love this country and this skin even when the world forgets how.

Maybe that’s what freedom truly looks like. Not purity, not apology, but peace.

Maybe it’s time to stop defining who we are by what we’ve suffered, and start loving who we’ve become.

Read More