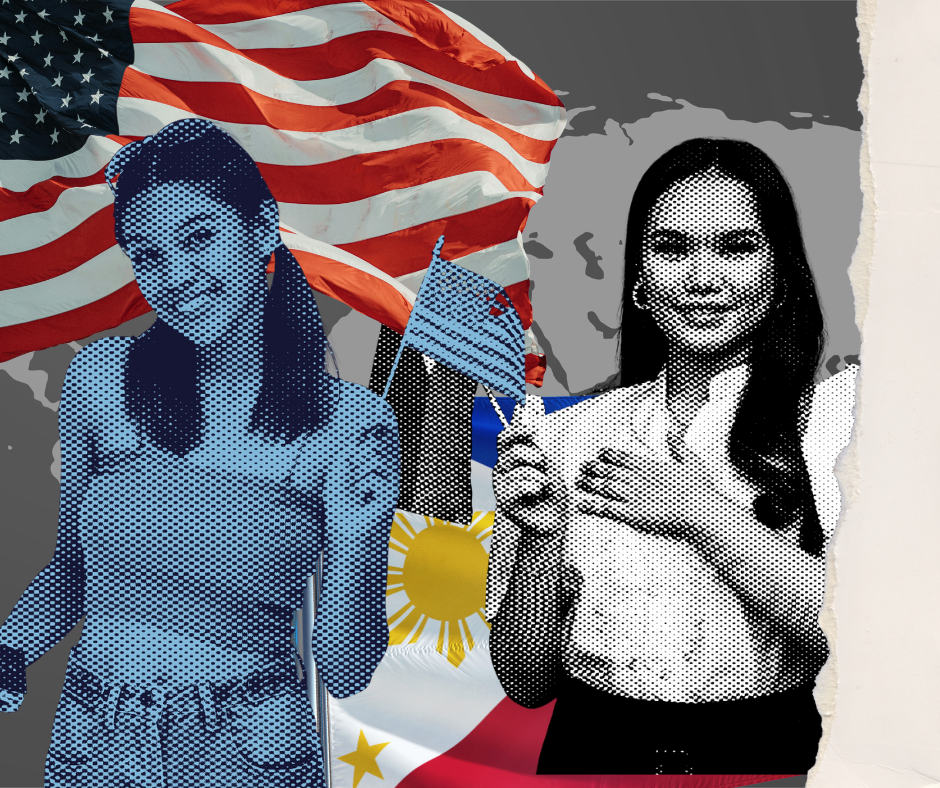

Not the Same: Why Being Filipino Is Different from Being Filipino American - and Why That Gap Matters

Being Filipino isn’t the same as being Filipino American - and that’s okay.

Written By Clifford Temprosa

To call someone Filipino is to describe more than ancestry. It is to speak of place, history, survival, and the daily realities that shape who we become. Yet too often, we collapse “Filipino” and “Filipino American” into one neat identity - as though oceans, empires, and generations of lived experience can be erased with a hyphen.

The truth is harder, and more honest: being Filipino and being Filipino American are not the same. Flattening them together does not build unity - it erases it. One identity is formed in the crucible of a homeland scarred by dynasties, corruption, and poverty; the other is forged in America’s assimilation wars, where invisibility and racial hierarchies decide who belongs. To pretend these experiences are interchangeable is to weaken both. True solidarity begins not with denial, but with difference.

And this conversation matters now more than ever. In a world where diaspora voices increasingly shape international policy, culture, and even elections, how we define Filipino-ness is not just an identity question - it is a power question. Global migration crises and the rise of identity politics demand clarity: who we are, and how we stand together, will determine whether Filipinos are seen as fractured and invisible, or as a global force with shared dignity.

Two Struggles, Two Contexts

Step into the streets of Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao and you will find youth activists risking arrest to fight dynastic politics, corruption, and staggering economic inequality. Their struggle is rooted in the material conditions of the homeland: public hospitals where patients line hallways for lack of beds, schools where overcrowded classrooms force students to share chairs, and communities where poverty is inherited like a family heirloom. In the homeland, silence is often survival.

Cross the Pacific, and the fight shifts. In San Francisco, Chicago, Las Vegas, and Queens, Filipino American students sit in classrooms where their history is absent from textbooks. They grow up pledging allegiance to an American flag while being told, in subtle and overt ways, that they are perpetual foreigners. Their struggle is not against political dynasties but against erasure, assimilation, and racism that insists they are outsiders in the only country they have ever called home. In America, silence is erasure.

Both struggles are real. Both require resilience. But they are not the same.

Inequity Is Shared, But Symbolized Differently

Inequity and inequality are not unique to one side of the ocean; every diaspora knows them. But their symbols and scars differ by geography.

● In the Philippines, inequality is made visible in the contrast of gated subdivisions towering over informal settlements, or in the cycle of political dynasties who treat poverty as both a campaign tool and a business model. Poverty makes community necessary.

● In the U.S., inequity looks different. It is racial profiling in airports, glass ceilings at work, the loneliness of being “too Asian” for America yet “too American” for the Philippines. Privilege makes individuality possible.

Inequity may be a shared condition, but its form and weight are never the same.

The Privilege of Liberal America

There is also the matter of privilege. The privilege of being raised in America with access to conversations, rights, and debates that homeland Filipinos can only imagine.

In the U.S., reproductive justice and abortion rights, though contested, are visible issues fought in courts, legislatures, and public squares. In the Philippines, abortion remains criminalized, forcing women into silence or unsafe procedures.

In the U.S., queer rights and protections exist, uneven but real, with marriage equality upheld by law. In the Philippines, queer lives are still debated in whispers, often tokenized rather than respected, and legal protections remain aspirational.

These are not minor differences. They shape values, worldviews, and expectations. For homeland Filipinos, liberal freedoms can appear like luxuries - while Filipino Americans often fail to recognize how rare those freedoms are.

Western Attitudes vs. Core Filipino Values

Another fault line lies in the everyday attitudes we carry.

● Filipino Americans, raised in the U.S., often embody Western values of individualism, self-expression, and achievement. They are taught to “stand out,” to pursue personal success, and to measure worth through visibility and career milestones. Identity is something to assert and defend in a multicultural battlefield.

● Filipinos in the Philippines, by contrast, are shaped by core cultural values:

○ Pakikipagkapwa (shared humanity) – seeing oneself in relation to others.

○ Hiya (a sense of shame or propriety) – a brake on behavior that prioritizes harmony over confrontation.

○ Utang na Loob (debt of gratitude) – obligations to family and community that outlast individual preference.

○ Bayanihan (collective spirit of helping) – a communal ethic where survival depends on the strength of the group.

To the homeland Filipino, the American insistence on “personal choice” can look selfish, disconnected from community obligations. To the Filipino American, homeland attitudes can feel restrictive, silencing, or resistant to change.

These differences in values are not just cultural quirks. They shape politics, family expectations, and even how each side defines freedom.

Symbols That Divide Us

Even symbols, the ways we perform identity, expose the gap.

In the diaspora, the term Filipinx has been embraced by some as a step toward gender inclusivity. For many in the homeland, however, it feels like a U.S. and Western centric imposition, linguistically awkward and culturally distant. What reads as progress in California can feel like erasure in Quezon City.

In the diaspora, Filipino flags are stitched onto sneakers, splashed across hoodies, and branded into merchandise. For Filipino Americans, these are declarations of pride in a country that erases them. But in the Philippines, the flag is sacred, reserved for ceremonies and state functions, not consumer branding.

The same flag that binds us in history divides us in meaning - sacred cloth in Manila, stitched fashion in New York.

Neither side is wrong. But each side fails to see the other’s truth.

The Foreigner and the Model Minority: Different Mirrors

Perhaps nowhere is the gap clearer than in how each community interacts with the idea of the “foreigner.”

● In the Philippines, many Filipinos project the “perpetual foreigner” stereotype onto others - especially Chinese immigrants and Chinese Filipinos. Discrimination against them is normalized, painting them as outsiders even after generations of belonging. Ironically, the very prejudice that diaspora Filipinos fight against in the U.S. is reproduced at home.

● In the United States, Filipino Americans are placed under the “model minority” myth: praised for being hardworking, silent, and assimilable while simultaneously excluded from true belonging. Organizing in the U.S. has taught Fil-Ams that no Asian ethnic group survives alone - that solidarity across Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, South Asian, and Pacific Islander communities is not optional but necessary.

The result is a paradox: homeland Filipinos perpetuate exclusion against Chinese-Filipinos, while diaspora Filipinos learn to dismantle exclusion through Asian solidarity. One community reproduces hierarchy; the other resists it. Both are shaped by their surroundings.

Assimilation and the Trauma of Migration

Between the homeland and the diaspora lies a rarely examined fault line: the lives of Filipinos who migrate as children or adults. Their journeys expose just how jagged the path between “Filipino” and “Filipino American” can be - and how migration itself becomes a wound carried across generations.

For the young, childhood becomes a battlefield of language, accent, and memory. The first day in an American classroom often begins with the slow erasure: teachers urging them to “speak English only,” classmates mocking the rhythm of their Tagalog or Ilocano, lunchboxes of adobo or tuyo turned into punchlines. What once felt like home-cooked love becomes a mark of difference. Belonging demands sacrifice, and the price is steep: a heritage silenced for survival.

For adults, the rupture is no less sharp. Nurses, engineers, and teachers - highly trained and respected in the Philippines - arrive in America only to find their degrees dismissed, their accents ridiculed, their expertise doubted. They are declared “overqualified” for the jobs available and invisible in the society they help sustain. Many live with a double burden: sustaining families back home while navigating a country that does not fully see them. Assimilation here is not just cultural. It is economic, professional, and deeply personal.

But migration does not move in one direction. Filipino Americans who return or relocate to the Philippines confront another paradox: culture shock in the very homeland they imagined as theirs. Their Americanized accents, habits, and liberal attitudes mark them instantly as different. Codes of respect, expectations of deference, and communal obligations can feel foreign after a lifetime in the U.S. They arrive seeking belonging, only to find themselves outsiders in the land of their ancestors.

And yet, privilege shadows them. The conversion of dollars to pesos stretches their wealth farther, offering comforts that many homeland Filipinos cannot afford. Their exposure to U.S. liberal values - on reproductive rights, queer rights, or free expression - arms them with confidence that can inspire admiration in some and provoke resentment in others. They are progress to a few, intrusion to many.

This is the paradox of reverse migration: Filipino Americans may feel dislocated in the homeland, yet they also embody a privilege - economic, cultural, ideological - that homeland Filipinos cannot ignore. They are both alien and advantaged, both estranged and empowered.

Assimilation trauma, then, is not only about what is lost when Filipinos enter the U.S. - the accents muted, the expertise undervalued, the childhoods reshaped. It is also about what is complicated when Filipino Americans return: their presence reshuffling hierarchies, their privilege sparking tension, their very identity reopening the question of what it means to belong.

Migration is never just movement. It is rupture, re-entry, and redefinition - an inheritance of both scars and privileges carried across oceans.

Why Flattening Hurts Us

Flattening our identities into one story doesn’t create unity, it creates fractures that fester.

When homeland Filipinos dismiss Filipino Americans as outsiders - “not really Filipino” - they erase decades of diaspora struggle: the racism endured in classrooms where they were invisible, the assimilation wars fought in workplaces that demanded they shed their accent or name, the quiet resistance of families who had to prove their worth just to belong. To deny them Filipino-ness is to deny the scars they carry from being treated as perpetual foreigners in the only country they know.

When Filipino Americans, in turn, romanticize the homeland as a backdrop for nostalgia - of fiestas, beaches, or balikbayan summers - without grappling with poverty, corruption, or fractured social systems, they trivialize lived struggles. A jeepney ride is not just “authentic culture”; it’s also the daily commute of someone who cannot afford private transport. A fiesta is not just colorful tradition; it’s often survival, a community pooling resources when the state has failed.

“Eating adobo doesn’t make you Filipino. But dismissing Fil-Ams as outsiders erases their fight too.”

The consequence is predictable: resentment. The diaspora feels invalidated, accused of being impostors in their own heritage. The homeland feels misunderstood, caricatured as a cultural museum rather than a living, struggling nation.

Solidarity dies not in violence, but in silence - the silence that grows when both sides refuse to see the other’s truth.

Naming the Difference

To build bridges, we must first name the rivers that divide us.

● Homeland Filipinos: Defined by dynasties, systemic poverty, underfunded schools and hospitals, and cultural values of interdependence - pakikipagkapwa, utang na loob, and bayanihan as survival strategies.

● Filipino Americans: Defined by assimilation and invisibility, racial hierarchies, model minority myths, and Western values of individualism, visibility, and achievement. Their fight is about recognition in a society that erases difference.

● Homeland mirrors: Prejudice projected onto Chinese immigrants and Chinese-Filipinos, treating them as “perpetual foreigners” in their own birthplace.

● Diaspora mirrors: Solidarity forged with other Asian and Pacific Islander groups, learning through organizing that survival requires collective resistance across ethnic lines.

● Intergenerational gap: In the Philippines, survival often means silence, obedience, and endurance. In the U.S., second- and third-generation Fil-Ams are taught to speak up, organize, and demand recognition - sometimes seen as arrogance by their homeland relatives.

Neither identity is “more authentic.” Both are products of history and geography. Both are valid, both are complex, and both demand respect. Not judgment.

Imagine grandmother in Zamboanga, standing in line for subsidized rice, the weight of poverty etched in her back as she waits her turn. Thousands of miles away, her U.S.-born granddaughter addresses a school board in California, demanding that Filipino history be included in the curriculum. One fights for survival, the other for recognition. Both fights matter. Both carry the same bloodline. Both are Filipino.

Beyond the Hyphen

To conflate these realities is to weaken them. To honor their differences is to make them stronger.

Solidarity does not come from pretending the Filipino in Manila and the Filipino American in Chicago share the same story. It comes from admitting that they don’t - and choosing to stand side by side anyway.

Being Filipino isn’t the same as being Filipino American - and that’s okay. Solidarity starts with difference, not denial.

If we are serious about building global Filipino power, we must stop flattening each other into a single narrative. We must learn each other’s battles, respect each other’s values, and honor each other’s contradictions. Migration is a rupture; identity splits across oceans. That rupture does not have to be permanent - it can be a bridge.

But let us be clear: if we fail, we risk becoming a fragmented people, erased at home and overlooked abroad. If we succeed, we can create a global Filipino identity that is not weaker for its contradictions but stronger because it embraces them.

Solidarity is not automatic. It is built. It begins with honesty about difference, grows through humility to learn each other’s truths, and flourishes when we recognize that our struggles - though distinct - are connected by the pursuit of dignity and justice.

Only then can we claim a solidarity worthy of our people.

Jimuel Pacquiao’s pro debut ends in a majority draw, raising big questions about legacy, pressure, and the first steps of his boxing journey.